An immersive, experiential work dedicated to the extinction of languages.

Now touring globally in conjunction with the UN/UNESCO decree naming

2022-2032: THE INTERNATIONAL DECADE OF INDIGENOUS LANGUAGES.

Created in collaboration with The Endangered Languages Documentation Programme and The SOAS World Languages Institute, SOAS, University of London and Marilyn and Jim Simons Foundation.

It is co-presented by UNESCO and The Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger

Last Whispers is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization.

Every two weeks the world loses a language.

At an unprecedented speed, faster than the extinction of some species, our

linguistic diversity—the very means by which we know ourselves—is eroding.

Today out of the 7,000 languages remaining on Earth, only 30 are spoken among

the majority of the world population. It is estimated that at least half of the planet’s

currently spoken languages will have died out by the end of this century.

Some estimates project a much greater speed of disappearance.

Last Whispers is a project about the mass extinction of languages.

By definition, this extinction occurs in silence, since silence is the very form it takes.

Last Whispers sounds what has gone silent.

While we drown in the noise of our own voices—uttered within dominant

cultures and languages—we are surrounded by a vast ocean of silence.

Last Whispers aims to further awareness of linguistic extinction.

MISSION

THE WORK

Last Whispers is an experiential, immersive work dedicated to the extinction of languages.

Last Whispers is an incantation of extinct and endangered languages. It is both a profoundly modern and a traditional choral work. The spatialized sound composition layers recordings of speech, recitatives, incantations, songs and ritual chants, with audible punctuations of sounds from nature and outer space frequencies (made audible), including gravitational waves of supernovas (dying stars) recorded by LIGO, “The Listening Ear.”

The result is a visceral, sensory immersion when experienced in any of the formats offered: a fully immersive gallery projection, an audio video theater installation, a virtual reality experience, or a dome projection.

The impact of Last Whispers is amplified through its use of cutting edge image and sound design and technology. Visually, the audience is dropped into landscapes and symbols devoid of people, as human voices call from deep space. The immersive and spatialized sound projection (available in binaural / 54.1 / 8.1 octophonic / 7.1 / 5.1 mixes), is interpreted by the human ear as a distinct 360° soundscape. This enveloping visual and sound environment prompts the brain to perceive the voices in the piece as “present” and “real.” Whether experienced as a video, as a virtual reality, or as an immersive projection mapping render or dome or sphere, the audiences find themselves inside the artwork for 30 minutes.

Courtesy of The British Museum, 2016

Premiere of Last Whispers in The Living and Dying Gallery

IMMERSION THROUGH ENGINEERING, INNOVATION AND TECHNOLOGY

Last Whispers was created in the UNREAL ENGINE, the world’s most open and advanced real-time 3D creation tool. The creation of the work in fact generated innovation as processors were built to catch up with its size and speed.

Last Whispers was mixed at the ALLOSPHERE, the only facility in North America with 360° full projection spherical mapping capability and 54.1 (separate channel) speakers.

While the art world has begun to show “immersive” experiences, such as Immersive Van Gogh, or Cézanne, the Lights of Provence, those are 2D projections that blanket a room floor to ceiling. Last Whispers is in a class by itself in that it is projected as engineered—it is engineered for immersion.

FORMATS

Last Whispers is produced in the most current experiential formats making exhibition accessible and flexible to any environment or venue.

Each format utilizes the most breakthrough, innovative in technology promising the greatest depth of immersion for audiences into an experiential artwork available today. Museums, galleries and performance spaces with fully immersive room projection (like IMAX) can exhibit the fully immersive experience in their spaces and/or host viewings within headsets. Other venues will be able to show an AV “film” and immersive sound format.

Running time for all formats: 30 minutes

PROJECTION MAPPING

for museums, domes, planetariums, spheres with immersive projection capacity & set up

54.1/8.1/7.1/5.1/binaural audio mixes

GALLERY / ROOM / CUBE

DOWNLOAD GALLERY / ROOM / CUBE

TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS

SPHERE

*SITE SPECIFIC TECHNICAL REQUIREMENTS

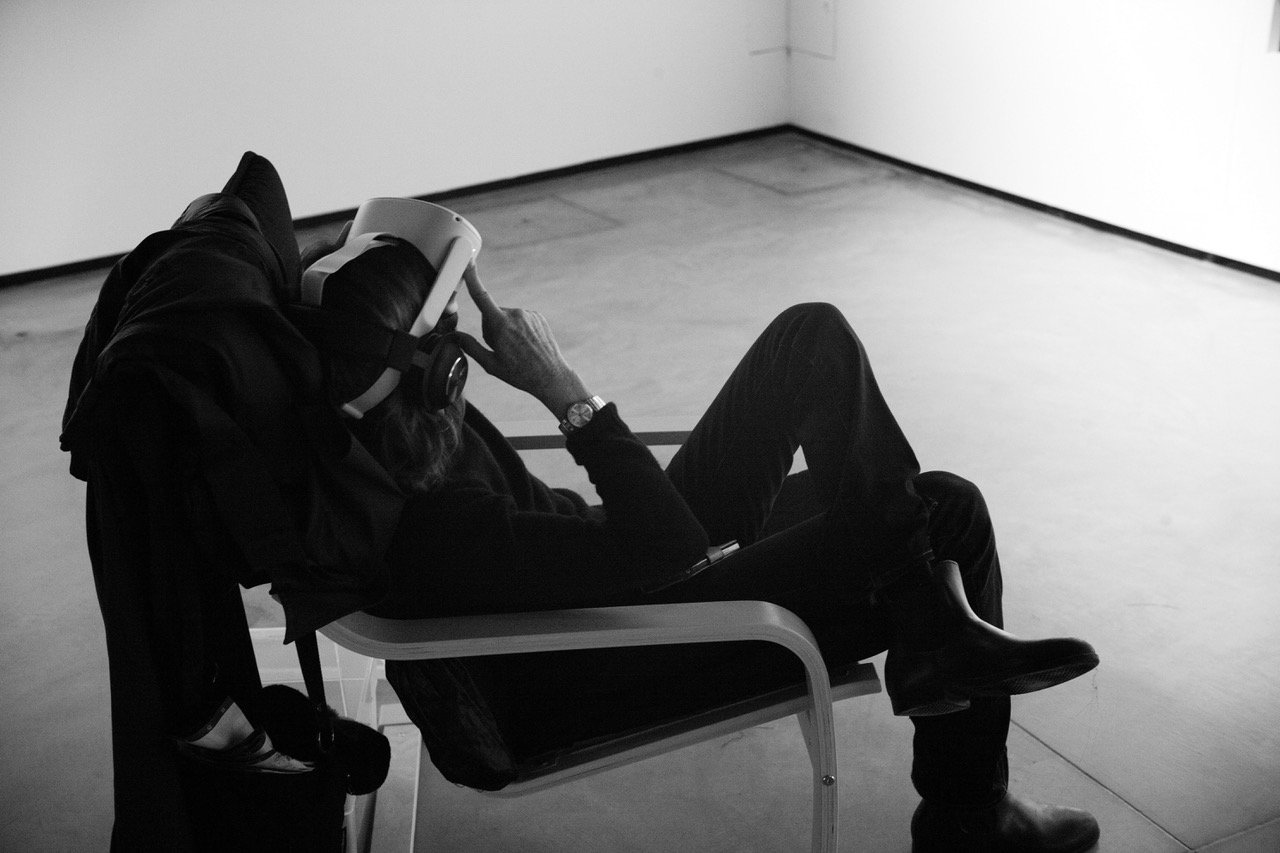

VIRTUAL REALITY HEADSET

for venues with virtual reality Oculus hardware (10 headsets are provided)

360 Playback Video ambisonic sound

AV / FILM INSTALLATION

2D film for concert halls, theaters and museums with movie projection capacities

spatialized sound 8.1 / 7.1 / 5.1 & binaural audio mixes

LAST WHISPERS, Kennedy Center, 2019

LAST WHISPERS, 2022

Art Night Screening, Venice, Italy

AWARDS

OFFICIAL SELECTION

SHOWS

VENICE ART BIENNALE

2022 Tour Launch

21 April - 25 September 2022

Co-presented by UNESCO.

Venice, Italy

3-PART SHOW:

VIRTUAL REALITY

30 minutes

CZF (Ca’ Foscari Zattere/Cultural Flow Zone)

Zattere al Pontelungo

THE ART NIGHT

30 minutes

Last Whispers featured as large scale outdoor projection

MURAL INSTALLATION

Main courtyard of Ca’Foscari

Palazzo Ca’Giustinian

Dorsoduro 3246, Venice

LAST WHISPERS PRESENTATION AT UNESCO

41st Plenary Session of

UNESCO General Conference

Paris, France

18 November 2021

Speech by Lena Herzog during the Launch of the World Atlas of Languages

Future Vision Lab by Taiwan Contemporary Culture Lab, C-LAB

Hualien, Taiwan

Presented by C-LAB

23 December 2022-5 March 2023

Dome (30 min)

Dome Fest West

Costa Mesa, California

October 2022

Dome (30 min)

WINNER Best Artistic Feature 2022

Théâtre du Châtelet

Paris, France

Presented by Le Festival d’Automne and Théâtre de la Ville in collaboration with UNESCO

21 November 2019

AV Immersive Oratorio Installation (45 min)

Latino Media Fest

Los Angeles, CA

28 September 2019

VR (7 min)

IDFA 2019

Amsterdam

20 November - 1 December 2019

VR (7 min)

Los Pinos Presidential Palace

Mexico City, Mexico

31 October 2019

AV Immersive Oratorio Installation (45 min)

DTLA Film Festival Dome Film Series

Los Angeles, CA

21 October 2019

VR (7 min)

Best 360 Film

43rd São Paulo IFF Realidade Virtual

São Paulo, Brazil

17-30 October 2019

VR (7 min)

PEAK Performances at Alexander Kasser Theater

Montclair, NJ

16-20 October 2019

AV Immersive Oratorio Installation (45 min)

SFIFF – Santa Fe International Film Festival Virtual Cinema

Santa Fe, New Mexico

October 14-18 2019

VR (7 min)

George Eastman Museum

Rochester, NY

15 October 2019—4 January 2020

AV Immersive Oratorio Installation (45 min)

Montreal’s Festival du Nouveau Cinéma

Montréal, Québec

7-18 October 2019

VR (7 min)

PRIX CINÉMA VR (FORMERLY PRIX IMMERSION) - FNC EXPLORE

Best virtual reality 360 film

New York Film Festival Convergence Program

New York, New York

27 September - 13 October 2019

VR (7 min)

The REACH at the Kennedy Center

Washington, DC

7-22 September 2019

VR (7 min)

Official selection and special presentation at the REACH Opening Festival

World XR Forum

Crans-Montana, Switzerland

5-9 September 2019

VR (7 min)

SandBox Immersive Festival

Qingdao, China

24-27 June 2019

VR (7 min)

Games 4 Change Immersive Cinema

New York, New York

17 June 2019

VR (7 min)

Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA)

15 June 2019

VR (7 min)

and Conversation with LACMA Director Michael Govan

Ford Theater

Los Angeles, CA

Co-presented by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) and by the Natural History Museum (NHM)

14 June 2019

AV Immersive Oratorio Installation (45 min) and Conversation with Paul Holdengräber and panel

VR HAMBURG

Hamburg, Germany

5 - 13 June 2019

VR (7 min)

WSIS Forum 2019

Geneva, Switzerland

8-12 April 2019

VR (7 min)

Official selection and special presentation at the World VR Forum

South by Southwest (SXSW) Festival

Austin, TX

8-17 March, 2019

VR (7 min)

Official Selection in competition at the Virtual Cinema Program

EarthX Virtual Cinema

Dallas, Texas

26-28 April 2019

VR (7 min)

The Kennedy Center and The Smithsonian

Terrace Theater (Millennium Stage Program)

Washington, DC

24 February 2019

AV Immersive Oratorio Installation (45 min) & VR (7 min)

Sundance Film Festival

Park City, Utah

25-29 January, 2019

PREMIERE of the VR (7 min)

Official selection, New Frontier Program

Royal Festival Hall

London

Presented by Royal Festival Hall & Southbank Centre, SOAS University of London & London Literature Festival

14 November 2017

AV Immersive Oratorio Installation (45 min)

Museum Fünf Kontinente München

Munich, Germany

Presented by Museum Fünf Kontinente, SOAS University of London & Literaturfest München

13 November 2016

AV Immersive Oratorio Installation (45 min)

PREMIERE

The British Museum

London

Presented by The British Museum, SOAS University of London & Bloomsbury Festival

21-23 October 2016

AV Immersive Oratorio Installation (45 min)

Last Whispers Premiere at The British Museum,

21 October 2016

Click to view slideshow of exhibitions

FACTS

Mandana Seyfeddinipur

Program Director of Endangered Languages Documentation Programme

Department of Linguistics SOAS, University of London

Today there are around 7,000 languages spoken worldwide, and at least half of those will have fallen silent by the end of this century. Globalization, urbanization, and climate change create economic, political, and social pressures on people, and in response, people give up their traditional ways of life, move to cities, and find new sources of income. In the process, they also give up their mother tongues and turn to other, typically more prestigious and dominant languages to foster economic and social mobility for their children. When languages are not transmitted to children, they become endangered and are likely to become extinct.

While speakers have shifted to other languages throughout human history, the speed of this development has dramatically increased over the past century. It is estimated that the loss of language diversity is happening on the scale of the fifth mass species extinction. Each of these vanishing languages expresses the unique knowledge, history, and worldview of its speaker community, and each is a distinctly evolved variation of the human capacity for language. Many of these languages have never been described or recorded, so their loss means the richness of human linguistic diversity is disappearing without a trace.

The statistics we have on the number of languages spoken in the world, and which ones are endangered, are only rough estimates because there is no reliable data for this issue. Today only 10–15 percent of the world’s languages are well described—meaning that very little knowledge has been accumulated for the other 85–90 percent of languages. By some estimates, there are 2,000 languages spoken in Africa and 800 in Papua New Guinea alone. It is estimated that in Australia there were 250 languages spoken at the time of European colonization. Today only 145 languages are left there, and 110 of them are critically endangered, which means that “the youngest speakers are grandparents and older, and they speak the languages partially and infrequently.” In a few years, only about 35 of the 250 original Australian languages will remain. The others will have become extinct.

Many factors must be taken into account when assessing language endangerment, as was described in 2009 by linguists M. Paul Lewis and Gary F. Simons. These include factors to assess language use in different domains of life, such as whether it is used only in the home or also in public; whether the language has a script; whether it is taught in schools; whether it is used in radio or TV broadcasting, or, nowadays, on the internet. But the key factor is intergenerational transmission: whether children learn and speak it. It is the children—what their parents and grandparents share with them and how they use the language in their daily lives—who make the difference. Once the line of intergenerational transmission is broken, it is hard to bring a language back to young people, whose daily lives are absorbed in the majority language.

Often it is these children, who can no longer speak to their grandparents, who come back later in life to search for their roots, trying to learn the language and understand their cultural heritage. Misconceptions about multilingualism, including ideas that learning many languages at once could confuse a child or be disadvantageous, lie at the heart of the problem, a problem that is social and political.

UNESCO Ad Hoc Expert Group on Endangered Languages. (—2003). Language Vitality and Endangerment, UNESCO,

Fishman, Joshua. (—1991). Reversing Language Shift: Theoretical and Empirical Foundations of Assistance to Threatened Languages. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters Ltd., 87-111.-

Hale, Kenneth; Krauss, Michael; Watahomigie, Lucille J.; Yamamoto, Akira Y.; Craig, Colette; Jeanne, LaVerne M. et al. (1992). Endangered Languages. Language, 68 (1), 1–42.

Lewis, M. Paul & Gary F. Simons. 2010. Assessing Endangerment: Expanding Fishman’s GIDS. Revue roumaine de linguistique55(2), 103–120.

THE ENDANGERED LANGUAGES MAP

LANGUAGES

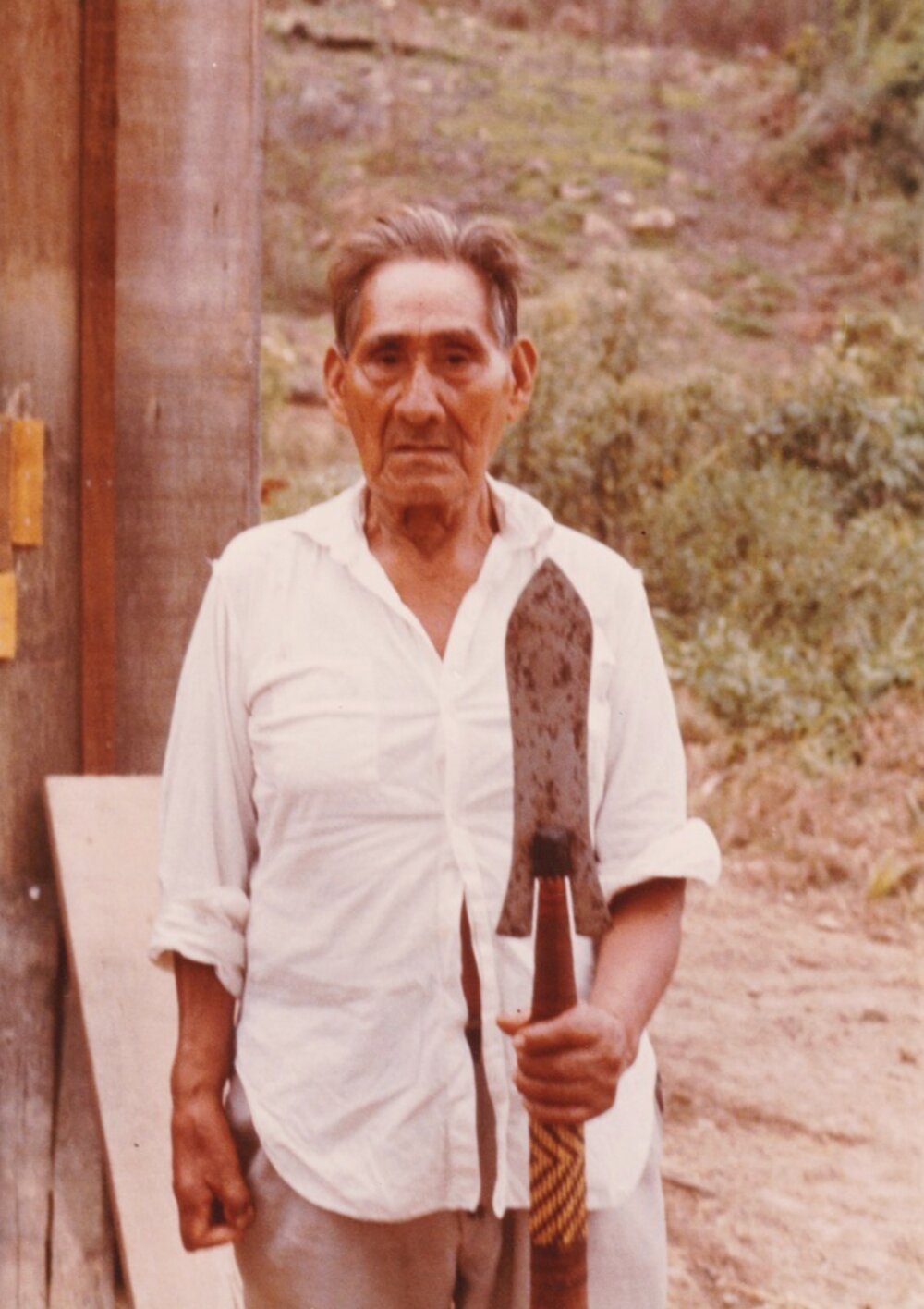

Below are the languages featured in Last Whispers, which were donated by last speakers, linguists, language activists and language archives. This collection of recordings was made in collaboration with the Endangered Languages Documentation Programme and the SOAS World Languages Institute, SOAS, University of London.

Ahom (India)

Pacific and Regional Archive for Digital Sources in Endangered Cultures (PARADISEC)

Collector: Stephen Morey

Speaker: Tileshwar Mohan

Ainu (Japan)

Endangered Languages Archive at SOAS University of London (ELAR)

Collectors: Anna Bugaeva and Hiroshi Nakagawa

Speaker: Mrs. Kimi Kimura

Ayoreo (Paraguay)

Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages

Collector: Anna Luisa Daigneault

Speakers: Iyagai Catalino Picanerai, Pehe Picanerai

Bathari (Oman)

Endangered Languages Archive at SOAS University of London (ELAR)

Collector: Miranda Morris

Speakers:

Maḥmūd Mšaʕfi Musallim Al Mashrami Al Baṭḥari, Sowma Zifena Musallim Al Mashrami Al Baṭḥari, Faraḥ Mšaʕfi Musallim Al Mashrami Al Baṭḥari, ʕᾹmir Māgid Suleyyim Al Mḥabši Al Baṭḥari, Nasra Salim Shemlān Al Mḥabši Al Baṭḥari, Salim Muḥammad Saqr Al Mashrami Al Baṭḥari, Rubeyyaʕ Adahaba Suleyyim al-Mamṭari Al Baṭḥari, Bakhayyit Saʕad Saḳr Al Mashrami Al Baṭḥari, Lḥabāb Hamūd Salim Al Mashrami Al Baṭḥari, Saʕad Qāsim Aṭali Al Mamṭari Al Baṭḥari, Salīma Saqr Laġafēli Al Mašarmi Al Baṭḥari

Central Balsas Nahuatl (Mexico)

Collector: Jonathan D. Amith

Speakers: Clemente Baltazar, Eugenio Castro, Valentina Reyes Damian, Silvestre Pantaleón, Mundo Ramírez

Chamacoco (Ishir Ibitoso) (Paraguay)

Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages

Collector: Anna Luisa Daigneault

Speakers: Baaso, Crispulo Martinez (Kafotei), Agna Peralta

Dalabon (Australia)

Endangered Languages Archive at SOAS University of London (ELAR)

Collector: Maïa Ponsonnet

Speaker: Maggie Tukumba

Duoxu (China)

Endangered Languages Archive at SOAS University of London (ELAR)

Collectors: Katia Chirkova, Zhengkang Han, Dehe Wang, Xiaowen Yuan

Speakers: Wenming Ma, Decai Wu, Denglian Wu, Rongfu Wu, Zhengmei Wu

Enxlet Norte (Paraguay)

Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages

Collector: Anna Luisa Daigneault

Speaker: Silvestre Martinez

Great Andamanese (India)

Endangered Languages Archive at SOAS University of London (ELAR)

Collector: Anvita Abbi

Speakers: Boa Sr., Buro, Ilfe, Pao Buddha

Ikaan (Nigeria)

Endangered Languages Archive at SOAS University of London (ELAR)

Collector: Sophie Salffner

Speakers: Lawrence Abiola, Comfort Adedeji, Dignes Adedeji, Hannah Adedeji, Richard Bamidele Adedeji, Fred Adekanye, Lydia Adekanye, William Adekanye, Mayowa Adekunbi, Ruth Adeoba, Juliana Adeyanju, Maybelle Adeyanju, Omojola Baale, Dorcas Babalola, Simeon Olaitan Balobun, Dorcas Balogun, Asya Gefter, Thomas Obadau, Janet Obanobi, Adesonmi Obaude, Bola Ruth Oloyo

Ingrian (Russia)

Endangered Languages Archive at SOAS University of London (ELAR) &

Karelian Institute of Language, Literature and History of the Russian Academy of Sciences

Collectors: Fedor Rozhanskiy, Elena Markus, Enn Ernits, Eino Kiuru, Elina Kylmäsuu, Terttu Koski

Speakers: Ekaterina Andreyevna Aleksandrova, Zinaida Antonovna Dmitriyeva, Aleksandra Mikhaylovna Efimov, Konstantin Efimov, Praskovya Milhaylovna Fedorova, Fekla Mikhaylovna Gerasimova, Evdokiya Isayeva, Evgokiya Lukinichna Ivanova, Tatyana Ignatyevna Ivanova, Akulina Mikhaylovna Kirilova, Nikolay Mikhaylov, Mariya Elizarovna Nikitina, Feodosiya Nikitichna Petrova, Evdokiya Filippovna Rodionova, Galina Ivanovna Samsonova, Anna Vasilyevna Stepanova, Anna Ivanovna Trofimova, Evgeniya Emelyanovna Vasilyeva, Matrena Dmitriyevna Vasilyeva, Mariya Volosanova, Anna Zolotova

Ixcatec (Mexico)

Endangered Languages Archive at SOAS University of London (ELAR)

Collectors: Denis Costaouec & Michael Swanton

Depositors: Denis Costaouec & Michael Swanton

Speakers: Juliana Salazar Bautista, Lirio Salazar Gutiérrez, María Patrocina Salazar Gutiérrez, Pedro Salazar Gutiérrez, Cipriano Ramírez Guzmán, Rufina Álvarez Robles

Ju|’hoan (Namibia)

Endangered Languages Archive at SOAS University of London (ELAR)

Collector: Megan Biesele

Speakers:|Ai!ae, ǁ’Angsa |’Angn!ao, |Asa ǁXamte, !Kaia G|aeku, Kaqece ǁ’Ao, |Kunta, N!aq’e, Nǁao Kxao, Sagǁai

Kotiria (Wanano) (Brazil and Colombia)

Endangered Languages Archive at SOAS University of London (ELAR) & Kotiria Linguistic and Cultural Archive

Collector: Kristine Stenzel

Speakers: Emilia Trindade Cabral, Helena Cabral, Mateus Trindade Cabral, Ricardo Trindade Cabral, Emilia Melo

Koyukon (USA)

Alaska Native Language Archive

Speaker: Henry Titus

Courtesy of Allen and Anne Titus

Laklãnõ Xokleng (Brazil)

The Archive of the Indigenous Languages of Latin America (AILLA)

Collector: Greg Urban

Speakers: Vãjẽky Téy, Vãjẽky Paté, Dil tõ vo

Courtesy of: Nanblá Gakran

Light Warlpiri (Australia)

The Language Archive, Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, Nijmegen, The Netherlands

Collector: Carmel O’Shannessy

Speakers: the children of Lajamanu

Los Capomos Mayo (Mexico)

The Archive of the Indigenous Languages of Latin America (AILLA)

Collector: Ray Freeze

Depositor: Yolanda Lastra

Courtesy of Joshua Freeze

Mani (Samu/Samou region of Sierra Leone/Guinea)

Endangered Languages Archive at SOAS University of London (ELAR)

Collector: Tucker Childs

Speakers: Momo Kaka Bangoura, Amara Camara, Kaba Camara, Yaaye Camara, Mahawa Conté

Manx (UK Manx)

Culture Vannin

Collector: Brian Stowell

Speaker: Ned Maddrell

Mbya Guarani (Paraguay)

Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages

Collector: Anna Luisa Daigneault

Nǁng (South Africa)

Endangered Languages Archive at SOAS University of London (ELAR)

Collectors: Tom Güldemann, Martina Ernszt, Sven Siegmund & Alena Witzlack-Makarevich

Project: A Text Documentation of Nǀuu

Speakers: Hannie Koerant, Andries Olyn, ǀUna Rooi, Griet Seekoei

Nafsan (South Efate) (Vanuatu)

Pacific and Regional Archive for Digital Sources in Endangered Cultures (PARADISEC)

Collector: Nick Thieberger

Speakers: Harris Takau and John Kalfau

Nivkh (Russia)

Sound Materials of the Nivkh Language

Collector: Hidetoshi Shiraishi (Sapporo Gakuin University)

Speakers: Konstantin Iakovlevich Agniun, Valentina Fedorovna Akilyak-Ivanova, Vera Eremeevna Khejn, Olga Anatol’evna Nyavan, Natalia Demianovna Vorbon

Olekha (Bhutan)

Endangered Languages Archive at SOAS University of London (ELAR)

Collector: Gwendolyn Hyslop

Speakers: Chey Go Chelong, Kuenga, Nakari, Singye

Ongota (Ethiopia)

Endangered Languages Archive at SOAS University of London (ELAR)

Collector: Graziano Savà

Speakers: Maale Goda, Gombo Karo, Dula K’awla, Geeda K’awla, Guayo Kurayo, Erre Sagane, Gename Wa’do

Paunaka (Bolivia)

Endangered Languages Archive at SOAS University of London (ELAR)

Collectors: Swintha Danielsen, Lena Terhart, Federico Villalta

Speakers: María Cuasase, Pedro Pinto, Juana Supepí, Miguel Supepí

Pite Saami (Sweden)

Endangered Languages Archive at SOAS University of London (ELAR)

Collector: Joshua Wilbur

Speakers: Anders-Erling Fjällås, Elsy Rankvist, Henning Rankvist, Tage Rankvist, Dagny Skaile, Per-Allan Steggo

Qaqet (Papua New Guinea)

Endangered Languages Archive at SOAS University of London (ELAR) and Language Archive Cologne at the University of Cologne

Collector: Birgit Hellwig

Speakers: Paul Alin, Rudolf Arum, David Landi, Joyce Laniat, Henry Lingisaqa, Francis Murum, Lucy Nguingi, Justin Samurl, Dorothy Singan, Marcela Tangil

Sadu (China)

Endangered Languages Archive at SOAS University of London (ELAR)

Collectors: Xianming Xu & Bibo Bai

Speakers: Lanzhen Li, Fenqin Li

Selk’nam (Ona) (Argentina)

Argentina

Selk’nam (Ona) Chants of Tierra del Fuego, Argentina, FW04176

Collector: Anne Chapman

Speaker: Lola Kiepja

Courtesy of Smithsonian Folkways Recordings (p) (c) 1972, used by permission.

Selkup (Russia)

Laboratory for Computational Lexicography, Research Computing Center, Lomonosov Moscow State University

Collectors: Olga Kazakevich & Leonid Zakharov

Speaker: Rodion Sergeevich Kubolev

Sumtu (Sone Tu) (Myanmar)

Endangered Languages Archive at SOAS University of London (ELAR)

Collector: Mai Ni Ni Aung

Speakers: U Lo Htaung, U Hla Sein, U Bo Thar, U Ni Tun

Surel (Nepal)

Endangered Languages Archive at SOAS University of London (ELAR)

Collector: Dörte Borchers

Speakers: Junkimaya Surel, Tikamaya Surel, Tirtha Bahadur Surel

Tehuelche (Argentina)

The Archive of the Indigenous Languages of Latin America (AILLA)

Collector: Jorge Suárez

Depositor: Yolanda Lastra

Speakers: Andrés Carminatti, Carmen Carminatti, Margarita Pocón de Manco, Ana Montenegro de Yebes

Trung (Dulong) (China)

Endangered Languages Archive at SOAS University of London (ELAR)

Collector: Ross Perlin

Speakers: Mon Jisong, Pung Svr, Wang Jici

Warlpiri (Australia)

Endangered Languages Archive at SOAS University of London (ELAR)

Collector: Carmel O’Shannessy

Speakers: Teddy Morrison Jupurrurla and the children of Lajamanu

Yanesha (Peru)

Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages

Collector: Anna Luisa Daigneault

Speakers: Christina Bautista, Justina Quinchuya

Yauyos Quechua (Peru)

The Archive of the Indigenous Languages of Latin America (AILLA)

Collector: Aviva Shimelman

Speakers: Victorina Aguado, Octavia Arco, Bautista Cárdenas, Macedonia Centeno, Delfina Chullunkuy, Soylita Chullunkuy, Ninfa Flores, Cecilia Guerra, Juana Huari, Soylita Huari, Saturnina M., Esther Madueño, Margarita Madueño, Lucia Pariunám Martínez, Santa Ellu Martínez, Genoveva Rodríguez, Lucía Rodríguez,, Leona Wamán, Urbana Yauri

Yoloxóchitl Mixtec (Mexico)

Endangered Languages Archive at SOAS University of London (ELAR)

Collector: Jonathan D. Amith

Speakers: Constantino Teodoro Bautista, Soledad García Bautista, Estela Santiago Castillo, Alberto Prisciliano Federico, Mario Salazar Felipe, Martín Salazar Felipe, Rey Castillo García, Martín Severiano Germán, Marcelina Encarnacion Gertrudis, Maximiliano Francisco Gonzalez, Fernando Niño Leonardo, Alfonso García Reyes, Victorino Ramos Rómulo, Lamberto García Santiago, Zoila Guadalupe Sierra, Maximino Meza Teodoro, Santa Cruz Tiburcio

STORIES

Last Whispers was made with painstaking attention to the cultural heritage law and, above all, to the ethical conduct in working with indigenous communities, linguists and archivists for each case. In addition, we invited them to contribute their stories which we began to run here:

The Sadu People

Culture and Language in Brief

In Memoriam

Díli Do Macuco (... - 1983)

Central Balsas Nahautl

Silvestre Pantaleón

Pite Saami

The Nuances of Reindeer

Paunaka

Documentation of Paunaka

Kotiria (Wanano)

The Kotiria of Amazonia

Great Andamanese

My Life with the Great Andamanese

Yoloxóchitl Mixtec

Prayer For a Change of Fortune

Trung (Dulong)

How to Read the Dictionary of an Endangered Language

Qaqet

The Qaqet of Raunsepna

Northern Paiute

More Than Words

Duoxu

Duoxu

Ahom

Ahom Language Work

Nivkh

Sound Materials of the Nivkh Language

Dalabon

Dalabon Language of Arnhem Land

Mani

Mani Lament

Ju|’hoan

It Takes Both Sides of the Digital Divide: The Ju|’hoan Transcription Group

TESTIMONIALS

“Lena Herzog collaborated with many archives, archivists, curators, and communities to visualize the depth of loss of when languages are no longer spoken. Her work does not sensationalize this loss. It is respectful of the enduring efforts of communities working to reclaim their languages. She listens and responds to communities and professionals in all she does. This is especially apparent in the well-researched “FACTS” and representative “STORIES” section of the Last Whispers website, but is true of how she works in general.

It was a delight for the Smithsonian to work with her and the Kennedy Center to bring Last Whispers to the DC audience. It was a moving and captivating performance, and she, Mark Mangini and Marco Capalbo were very generous with their time in discussing the work with the audience and answering questions, sharing the stage with Smithsonian curators. Adding this context to their vision makes the oratorio and immersive VR experience truly art and truly educational as audiences more fully realize the trauma surrounding language loss. ”

—Mary S. Linn, Ph.D.

Curator of Language and Cultural Vitality

Director, Language Vitality Initiative

Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage

“Every recording in this oratorio has been given to Lena by the community, singers, scholars, or their descendants.

All wanted to share these incredible voices, and wanted them to be heard. Lena made that possible.”

–Dr. Mandana Seyfeddinipur

Director, Endangered Languages Archive & Endangered Languages Documentation Programme

Berlin Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities

PRESS

REACTIONS TO LAST WHISPERS

"… an unclassifiable work.

Ms. Herzog approaches this dismal subject in a decidedly poetic, almost abstract way, conveying the aura of all that’s being lost rather than haranguing. That we don’t see the speakers and can’t know what’s being said is the point of this austere and poignant Babel. The musical landscape is sometimes gentle, sometimes aggressive, but it always keeps our attention on the rich, incomprehensible, often overlapping chorus of words.”

—Zachary Woolfe, The New York Times

"A very haunting and singular experience.”

—Alex Ross,

music critic for The New Yorker magazine and author of The Rest Is Noise

"I sat back and…lost myself. I loved it....what I loved most was the conceit, and I mean conceit in the way Samuel Johnson meant, in other words, what I’m talking about here is the strategy. The work didn’t say, “Now, listen up folks. You really have to do something about the languages that are dying out all over our planet.” Whispers did something far superior. It gave us some languages (some spoken and some sung) and it asked us simply to immerse and lose ourselves in them. And by the time that process was over, 46 minutes later, it had won the argument (without raising its voice). Once you’ve heard these words, the words in this film, that are spoken by marginal peoples from all over the world, you know these languages must be nurtured and nourished and cherished and that that position is non-negotiable. Whispers put the case and collapsed the opposition. Game over as my children would say. Now that’s quite something to pull off in 45 or 46 minutes. A magnificent achievement and a magnificent work."

—Carlo Gébler, Irish poet, playwright and novelist

ORIGINS

LENA HERZOG ON THE ORIGINS OF THE PROJECT

Last Whispers, Oratorio for Vanishing Voices, Collapsing Universes, and a Falling Tree

At the age of six I decided to learn English so that I could understand a puzzle in a Sherlock Holmes story. I had to know how the detective had decoded a death threat to his client’s wife in The Adventure of the Dancing Men. The key to that puzzle was the recognition of the recurring definite article “the”—a mysterious notion to me then since articles do not exist in Russian. I grew up in the

Urals, on the western border of Siberia, where very few people spoke foreign languages. I picked up Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s original in English, along with a dictionary and a grammar text book, and struggled through the entire book line by line. Later, also prompted by the desire to read literature in the original, I studied French and Spanish and, worked as a proof-reader at a printing press in Saint Petersburg, next to the compositors that were busily nestling letters into words, words into sentences, and sentences into novels at a staggering speed, throwing proofs over to my table like hot bread. So it made sense to me that when I went to Saint Petersburg University, the door plaque of my faculty read “philology” φιλολογία—including the original Greek, which means “love of the word.” However, all my plans to become a Russian novelist were upended by a complete linguistic dislocation to American English at age twenty, when I moved to the United States. The sense of personal language loss was concrete and overwhelming, alerting me to a far more universal and dire fate for most languages.

The idea for a project specifically on the mass extinction of languages came to me more than two decades ago. My old failed 2003 Guggenheim application was titled “Vanishing Cultures” and was at first, in part, a photographic project. I’d planned to take large-format portraits of the last speakers of various languages and place them in a room filled with their whispering voices. The concept of sounding vanished voices by broadcasting them as a muffled chorus was already central and clearly articulated in my description of the project back then.

I realized that indigenous communities give up their languages and switch to dominant ones under pressure from the forces of globalization. My next natural iteration of this idea involved shedding the images of the speakers and having only voices in a forest. When a tree falls in a forest and no one hears it, does it make a sound? This old philosophical trope, the basic epistemological exercise, seemed handy. What is our sense of the unobserved, unheard worlds? I have come to think of this old exercise as one in empathy: Does it matter that trees and universes collapse all around us? Somewhere, between our obliviousness to others and our own inevitable oblivion, rest the scales of some brutal justice.

My team and I began amassing a giant library of recordings of extinct and endangered languages on loan from international archives, working closely with many collections, linguists, and anthropologists in the field. Our main collaborator was the Endangered Languages Documentation Programme, a project of SOAS University of London that is headed by Mandana Seyfeddinipur. When I went through their archives online, I realized there would be no point in just “stacking” languages back-to-back to form a single piece. Because these recordings were already public, generously so, it would have been possible to perform this kind of compilation just by clicking “next” on their website, and that would have been too obvious a gesture for the work I had in mind.

While working in my studio and darkroom, I created a setup that randomly played thousands of these recordings, one after another. I marked those that felt right for the oratorio I was planning and began narrowing down the library. The extraordinary researcher Theresa Schwartzman, in Los Angeles, and her counterpart in London, Eveling Villa, began reaching out to archives, linguists, and indigenous communities (when this was possible) to obtain rights and permissions for the recordings. Sometimes there was no community to reach. We went beyond the letter of the law, which held that the copyright resided with the linguists and the archives, and tried to reach those who claimed heritage to the language. Sometimes last speakers changed their minds, turning us down mid-composition and mid-film, and we had to redo the work from scratch, rescore and rethink. Each case had a story, most often a tragic one. We began to publish some of them on our website.

Every dialogue with a linguist, no matter how banal, brought insight. The professionals who travel and live among these last speakers are the unsung heroes in this story; they are the ones who collect, preserve, and help revitalize endangered languages. In my dealings with them, they were the advocates for the last speakers’ rights. One might think that they would number enough to form an army, but there are barely enough of them for a battalion. Most work alongside volunteers and language enthusiasts. And all of them, at least those that I have met, are on the side of indigenous peoples. To put it in espionage terms, linguists of endangered languages almost always “go native.” They are the ones who hear the trees falling in the forest. Our long list of credits names both the speakers and the linguists—meticulously.

The polyphonic global chorus that I heard had the makings of an astonishing oratorio, and to bring it into a public space beyond the form of the archive, I needed music and imagery that would reveal it in a condensed form. This form had to be invented organically; it had to come from the recordings, from the voices themselves.

Marco Capalbo and Mark Mangini, who work fluidly in both sound design and composition, joined the team, and we began to shape the oratorio from our already-narrowed library. My concept was multilayered and concrete: it included the use of sounds of Russian bells, forest noises, wind, interpreted gravitational waves from outer space registered by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (a.k.a. “the Listening Ear”), and the specific parameters for the source library itself. In my first brainstorming session about the work, I wrote to Marco and Mark:

What is the balance of the piece? What holds it together?

The “founding idea” of making the work is based on the recordings of languages that had already vanished or are well on their way to extinction. The parameters within which the selection was made for the source library—I have defined. This is clearly a glue as the overall idea and basic building blocks. … Using cosmic sounds of the universe within the composition expands the arc. Gives us “eternal” time. … I really love the opening with the bell. The end will have to be a giant chorus that builds and builds and then abruptly vanishes—in an exhale.

Shifting from fragmentation to a lyrical cradling of the voices, then back to fragmentation, and ending with a finale of interwoven harmony and dissonance were key to the piece I was constructing with my team.

Listening to the sounds of the voices and the first sketches by Marco and Mark, the photographer Tomas van Houtryve and I mapped a precise choreography of drone footage. Animator Amanda Tasse and I decided to create a new topography for the world that would have no “real” geography. We collected NASA images of hurricanes, cut out their edges, and sewed them together, forming something like a digital quilt to cover the earth. I thought that the edges of these vortices textured the continents and islands well, lighting the globe like a strange marble.

There is lamentation and melancholy in the oratorio. How can it be otherwise? And yet it is not a requiem—it is an invocation of languages that have gone extinct and an incantation of those that are endangered. I myself got addicted to these vanishing voices. I listen to them all the time now. They remind me that despite the deafening noise of our own voices, we are floating on an ocean filled with the silence of others.

NOTES ON COMPOSITIONS

BY MARK MANGINI

I felt that the best way to honor and respect the last speakers was to find the most compelling expressions of their individual languages and bring them to life in a modern, high-fidelity way. After combing through hundreds of hours of interviews, songs and chants, I selected 30 recordings that moved me the most and worked to bring them to life through the use of underscore, montage, and sound design. Though most of these archival recordings were captured monaurally and are of questionable fidelity, we designed an octophonic speaker system so to reproduce the recordings as immersively and experientially as possible. To show off this immersive space, I built an octophonic virtual sound environment in the studio and placed the last speakers within it. I felt that they should live in a world of sound that is as modern as the one we ourselves experience, thereby presenting their stories and songs in as lifelike a fashion as possible.

NOTES ON ORA

BY MARCO CAPALBO

ORA—the root of many words: the mouth, speaking, prayer, aura, a soft wind or breeze, and speech is of course connected to breath, and so to life itself. So here Ora is perhaps a breathing spoken prayer.

I used multiple processes in the composition of ORA. I generated sounds through purely electronic means, and I modulated natural sounds using a variety of techniques. The sound layers were arrayed in an eight-by-eight circle, then projected into eight discrete loudspeaker channels, like the rings of some kind of tree, each one bringing us closer to the center. Each loudspeaker is treated as an independent sound source, and sounds are projected and travel through the space in a variety of ways. All the sound was created more or less “from scratch” in a computer-programming language called CSound.

The sounds follow a progression from the cosmic-universal to the natural, the spoken to the sung, the sustained (cello harmonics) to the resonating (bells). The universal sounds are the most chaotic, the bells the most regular. Each of these six elements has its own rhythm, composed in sixfold counterpoint. Each has its solo moment, with the rhythmic proportions reflected in the large and the small. Voices were placed within a time structure in which they could sing and speak, together, alone, in synchronized groups and chaotic masses. I treated the different languages equally, not picking favorites. To this end, I drew upon a large pool of sound files—some 400 in all. The listener is guided into a sonic space where all the words and songs and cries and chants play within a forest of sound, free of meaning, in some mysterious vastness. While few listeners—and even fewer as time goes on—will grasp semantic meaning from the words, everything has the sound of humanness. We recognize the utterances of our brothers and sisters, as well as our shared ability to form sounds to communicate with each other. A variety of bell sounds toll a sixfold sequence of differently timed repetitions. Six bells start together, and they are one beat away from repeating at the very end of the piece, as each bell follows the other in sequence. So, if the piece were extended, the whole cycle would begin again, another breath in some great oscillation.